Dr Christin Eltze and Nicola Barnes, GOSH

Disclosures

- CE was PI for studies sponsored by GW Pharma

- CE has contributed to and chaired sponsored educational events

activities by GW Pharma and Nutricia (fees to departmental funds)

Tom

Syndrome diagnosis: Lennox –Gastaut Syndrome

- Birth history: uncomplicated (term NVD)

- Seizure onset: age 4 m → infantile spasms (responsive to VBT + Prednisolone)

- Seizure recurrence age 15 m → multiple seizure types (epileptic spasms, tonic sz drop sz)

- Evolution with global delay and profound intellectual difficulties, drug resistant epilepsy

- @ age 3 years:

- presurgical evaluation (CESS) – MRI: FCD right frontal lobe, ictal EEG (spasms)

variable lateralisation, subclinical seizures with onset either hemisphere - Pre-surgical counselling: 50 % chance of seizure freedom

- Right frontal lobe resection ( histology non-diagnostic )

- presurgical evaluation (CESS) – MRI: FCD right frontal lobe, ictal EEG (spasms)

- Seizure free for 3 months post surgery – then recurrence (multiple sz types incl drop

seizures) - VNS implanted age 6 years → no benefit in sz reduction

Tom – Progress – age 10 years

- Impaired mobility (unsteady gait – frequent drop seizures, required wheelchair)

- Communication: single words and gestures.

- Generally ‘happy’ but – Behaviour at times challenging:

- self-induced vomiting; episodes of screaming and

aggressive behaviour (pinching), Spitting

- self-induced vomiting; episodes of screaming and

- ASMs: valproate and clobazam

- Referred to back to CESS –

- underwent Corpus Callosotomy

Tom – post- Corpus Callosotomy

- Seizure free initially → more alert & socially engaging

- Mobility improved – walking independently at home

- 4 weeks post-op: refusal to eat and drink, non-compliance with ASMs

- Seizure recurrence (nocturnal seizures ) – hospital admission

- Required – feeding support with NG-tube and then gastrostomy

- 4 months post-op: increase of tonic seizures (nocturnal) + atypical absences

- Behavioural deterioration:

- aggressive behaviour, self-harming (head banging)

- Brain MRI – postoperative changes only, CC – complete; EEG – confirmed – not in

NCSE - Around the time underwent dental treatment under GA

- Behavioural deterioration:

Reasons for behaviour change, How we can support

- Prior to CAHMS referral all medical reasons for distress ruled out

- Have we woken up the child , now see true personality ????

Behavioural outcomes after Corpus Callosotomy

- Little information in literature

- Sharawat e al 2021, Child’s Nervous System (2021) 37:2557–2566 Efficacy and safety of CC and KD in LGS

- CC: 23 studies (436 patients)

- Average age at CC was 11.3 ±7.8 years, and the average time from seizure onset to CC was 8.6±6.9 years

- Average follow up 43.2±29.7 months.

- Seizure free: 40.78% (95%CI—28.24–53.33%); ≥ 50 % sz reduction 85% (anterior CC in 177/436)

- Only 5 studies assessed cognition and behaviour

- Improvement in behaviour and communication reported in 69%

Behavioural outcomes after Corpus Callosotomy

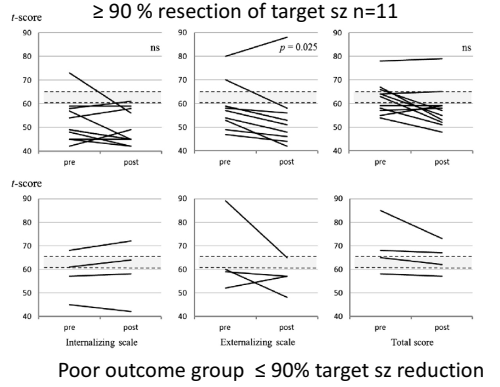

- Yonekawa et al, Epilepsy & Behaviour 22

(2011) 697–704 - N=15 retrospective (age 3.1-17.9 years)- target seizures – drop attacks (mostly LGS)

- Assessed with Child Behaviour Checklist :

- pre- and postoperative Attention Problems scores

showed no statistical differences between seizure

outcome groups - decrease in Externalizing scores for the patients

with a favourable outcome.

Lea, right handed, referred age 13 years

BMI > 99.6th centile

- Birth History: uncomplicated (term, NVD ); Early development – normal

- Seizure onset: age 2.5 years, prolonged left focal motor (25 minute duration)

- Focal seizures: aura: “stomach ache” evolving to bilateral tonic clonic seizures

- Drug resistant (failed 3 ASMs incl Levetiracetam not tolerated (aggressive behaviour)

- Learning difficulties – attends special school (does not like school)

- Behaviour: no behavioural concern, but peer-relationship difficulties – no friends

- Referred to CESS age 14 years, local brain MRI report 4– lesion negative (degraded by movement artefacts)

- Optimised MR imaging: right temporal lobe incl hippocampus/amygdala decreased grey/white differentiation,

- FDG-PET: right temporal hypometabolism

- VT-EEG : sz semiology – right mesial temporal onset, fear, preserved speech

- Neuropsychology: weakness in language , memory difficulties , ASD assessment recommended

- @ Age 16year 9 months: right anterolateral temporal lobectomy + amygdalohippocampectomy• (histology hippocampal sclerosis)

Low mood on discharge home

- Recovered well from surgery – discharged her on day 4

- Some anxiety observed before going home, reassurance given

- Post op call day 10: low appetite, refusing to leave bedroom , general lethargy, reporting abdominal aura but no sz

- 2 week post op: frequent calls from family, she was withdrawing from social media, crying +++ with one event of unresponsiveness, not typical of pre op events

- Review at GOSH for wound review – panic attack once home requiring local hospital assessment

- 4 weeks post op: psychiatrist review, low mood, no appetite, tearful, struggling to sleep , poor energy and no motivation. Was only settled if brought by father to GOSH reception to sit for a few hours every day and wished to be readmitted to hospital

Assessment and support

- Impression:

- Post-operative low mood, possibly adjustment reaction with generalised anxiety and a panic attack. This seems to be related to concerns about her feeling safe (on the ward) and some worries about her physical health (auras, pain and anxiety around seizures).

- Unable to facilitate readmission to ward, distraction techniques to encourage returning to usual activities she enjoys, cooking, TikTok

- https://www.nhs.uk/mental-health/children-and-young-adults/advice-for-parents/anxietydisorders-in-children/

- https://www.childline.org.uk/toolbox/calm-zone/

- https://hampshirecamhs.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Self-help-Workbook-Children-

1.pdf - Promotion of sleep hygiene

- Phased return to college

- Local CAHMS referral : sertraline prescribed, diagnosis of depression

Now

- 18 years old: continues on topiramate and sertraline

- Post op EEG captured ongoing abdominal pain, staring reduced responsiveness: not epileptic

- No seizures or aura reported since May 2024

- Dad reports that her mood is much better on sertraline

- She comes out of her room and mixes with the family and siblings

- She still can have low mood and can cry a lot. She can also get angry quickly, but laughs too

- There is ongoing CAMHS input

- She is happy she has lost weight

Psychiatric outcomes after temporal lobe surgery

De novo onset Depression

- Hue et al. Epilepsy & Behavior 134 (2022) 108853, Systematic review

- 18 studies, incl. patients > 18 y, patient numbers 49-230

- Variable assessment and measures, follow up 3m-9y

- Incidence 0 – 38% (many studies reporting improvement)

- Most within first year after surgery

- Risk factors (not primary aim)

- Pre-op: Pre-existing diagnosis + FH

- Post-op: family dynamics, patient adjustment, seizure control

Comorbid psychiatric disorder

- Ploesser et al, Epilepsy Research 189 (2023), Systematic review and meta-analysis

- 10 studies, children (1) + adults (8), both (1)

- Participants 22-115 (total 496)

- Follow up mostly 2 years (range: 1m-30y)

- Wide range of results

- Overall 43% improvement

- 33% worsening (adults 19-21%, Children 7-36%)

Do behavior and emotions improve after pediatric epilepsy surgery? A systematic review

C Reilly et al (Epilepsia. 2019;60:885–897.)

- 15 studies included (mostly High Income Countries)

- 12 of 15 TLEs surgery, ample size 28-100, 4/15 had control group

- 12/15 used standardised tools (CBCL, SDQ)

- Quality: 5/15 – moderate, 10/ 15 weak

- No study noted deterioration of behavior

- Studies using DSM – no significant change of children diagnosed at baseline and follow up (resolution of diagnosis in 21 and in 16 new diagnoses)

- Better seizure control associated with improvement

Pre surgical assessment

- CESS pathway allows neuropsychology testing of cognition, memory and language

- Neuropsychiatry assessment of mood of family, expectations for surgery, mood, may ask local CAHMS for involvement to support further diagnosis assessment of ASD, ADHD

Self injurious behaviour following epilepsy surgery

- SIB defined as self inflicted non accidental acts causing damage or destruction of body tissue, carried out without suicidal ideation or intent: self biting , self hitting , teeth grinding , object finger in cavities and hair pulling

- Assessment: psychiatric history , social needs and risk assessment

- Rule out medical causes , depression and ADHD, hyperactivity, impulsivity

- SIB can be chronic or refractory, premise for behaviour can be maintained by socially medicated reinforcement i.e. acquisition of instrumental/communicative functions, or alternately by automatic reinforcement, i.e. that there is a sensory seeking component. There is always a reason for challenging behaviour. It may not be easy to see at first. It is the child’s best attempt at telling you something.

Interventions

- ADHD, stimulant medication is generally safe and effective in children with epilepsy

- Positive Behavioural Support (PBS) patient centred, individualised approach, MDT support essential

- Functional Assessment: Aim to identify events that typically precede and follow episodes of self injury in order to form a hypothesis regarding factors eliciting and maintaining the behaviour. Use of an Antecedent–Behaviour–Consequence (ABC) checklist.

- Intervention

- Short term Non Contingent reinforcement

- Long term Implement a PBS traffic light system

- Green, keep child in green zone when behaviour is regulated, simple communication, positive reinforcement, set boundaries with PECS, visual planners, routine and structure

- Amber, recognise early warning signs, give the child what they want, divert or distract, do not respond if safe to do so, stay calm

- Red, behaviour is happening, divert, distract, low arousal approach, calm, regulate breathing, personal space

Pharmacological Management (Claire Eccles)

- Pharmacological Management- Consider STOMP/STAMP. Limited meta-analysis evidence for both antipsychotics or ASM and SIB unlikely to respond. Review NICE guidance.

- The guidance is clear that antipsychotic medication should only be used for challenging behaviour if:

- Psychological or other interventions alone do not reduce the challenging behaviour within an agreed time, or

- Treatment for any mental or physical health problem has not led to a reduction in the behaviour, or

- The risk to the person or others is severe (for example because of harming others or self-injury).

- General principles:

- Identify target behaviour, Start low and go slow (increased risk of EPSEs and NMS), Regular review after 3-4 weeks, Stop medication if no response in 6 weeks.

- Risperidone is licenced for short-term use (up to 6-10 weeks) for persistent aggression.

References

- Yates, TM (2004) The developmental psychopathology of self-injurious behavior: compensatory regulation in posttraumatic adaptation. Clinical Psychology Review, 24: 35–74.10.1016/j.cpr.2003.10.001

- Biswas A, Gumber R, Furniss F. Management of self-injurious behaviour, reducing restrictive interventions and predictors of positive outcome in intellectual disability and/or autism. BJPsych Advances.2023;29(5):337-341. doi:10.1192/bja.2022.49

- NICE Guidance [NG11] Overview | Challenging behaviour and learning disabilities: prevention and interventions for people with learning disabilities whose behaviour challenges | Guidance | NICE